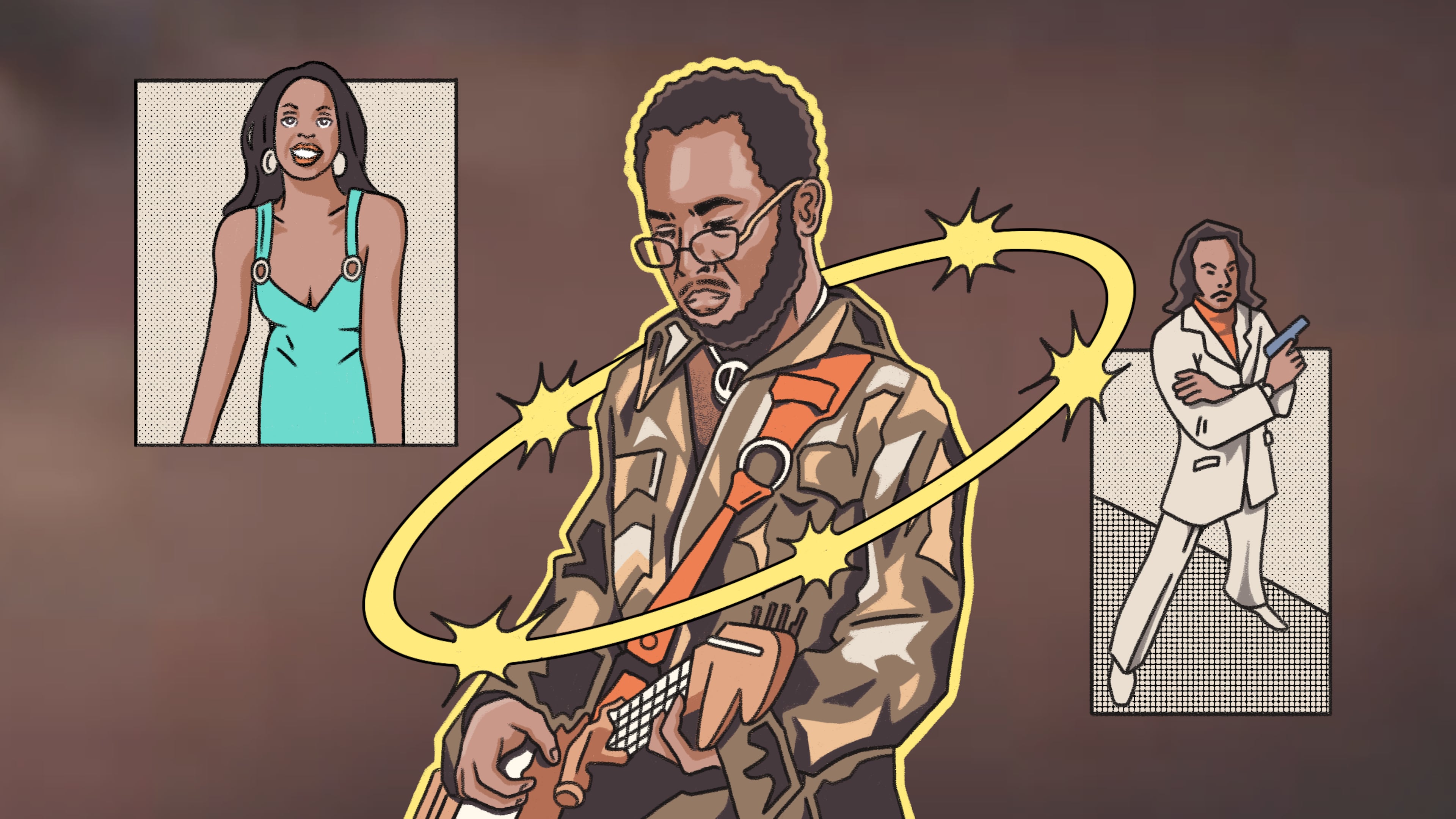

Curtis Mayfield turns Atlanta and Blackness into music for classic films

Throughout the 1960s, Curtis Mayfield achieved success as a songwriter, producer, guitarist and lead singer of R&B vocal group the Impressions.

The Chicago-based trio became popular with romantic ballads “I’m So Proud” and “It’s All Right.” Their songs “People Get Ready,” “Keep On Pushing” and “We’re a Winner” became civil rights anthems.

By 1970, Mayfield wanted to pivot. The prolific falsetto left the group to pursue a solo career and start his record company, Curtom Records, to have creative freedom and release songs of substance.

He went on to be inducted into multiple halls of fame, including twice in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, as a group member and solo artist, and the Georgia Music Hall of Fame.

The Grammys presented him with its Legend Award in 1994 and its Lifetime Achievement Award the following year.

His penchant for combining social commentary with percussive grooves earned Mayfield induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1999. Even Barack Obama featured the Impressions’ “Keep on Pushing” during his 2004 Democratic Convention keynote speech.

“He felt he had to remain commercial to get his name out there and make music that uplifted Black people. Film soundtracks and message music are some things he’s always wanted to do,” Mayfield’s son, Cheaa, 46, told UATL.

The singer and songwriter was able to incorporate socially conscious subject matter in his original compositions for film.

“Super Fly,” his debut soundtrack, was released in 1972. The movie is about a charismatic drug kingpin who plans a scheme to get out of his lifestyle.

“Super Fly” was among the earliest films of the “Blaxploitation era,” a period during the early to mid-1970s with movies funded by major studios, set in the inner city, and starring Black actors portraying characters who challenge white antagonists.

Album cuts “Freddie’s Dead” and “Pusherman” had funky, percussive and soulful arrangements. Mayfield didn’t want to glorify the film’s subject matter and chose to write lyrics that were morality plays.

“He didn’t really care for the movie, because he thought it was a very long commercial for cocaine use. All the tunes on the soundtrack are uplifting, cautionary tales,” his son said.

Mayfield started his process for writing and composing for film by watching videocassette tapes with no sound effects numerous times. He worked overnight to complete songs before he recorded them.

“He did most of his writing late if something came to him. He wrote lyrics on several legal pads, sat on the floor in a little room surrounded by papers, and his guitar in his lap before he stepped foot in a studio,” Cheaa Mayfield said.

“He didn’t want to waste too much time trying to figure something out, because there were other artists renting out the studio to record their own music.”

“Super Fly” was released at a time when Black performers Issac Hayes, Marvin Gaye, James Brown, Barry White, Willie Hutch and Bobby Womack released solo albums and composed and scored original music for film. Cheaa Mayfield said his dad respected and understood his peers’ creative renaissance.

“He didn’t look at it as competing against other artists of the time, because he thought they were all on the same team,” he said.

In 1974, R&B group Gladys Knight — an Atlanta native — and the Pips recorded the soundtrack to “Claudine,” a love story starring Diahann Carroll and James Earl Jones about a poor single mother and garbage man in New York. Mayfield wrote and produced the album.

He returned the following year with “Let’s Do It Again,” the soundtrack to the comedy starring Bill Cosby and Sidney Poitier. Its title track, recorded by family gospel and soul group the Staple Singers, reached No. 1 on the Billboard pop and R&B charts.

In 1975, Curtis Mayfield purchased a home in Southwest Atlanta. He installed a recording studio, Curtom Records’ offices, and split his time between Chicago and Atlanta

Mayfield, who had 10 children, wanted to concentrate on fatherhood.

“He felt Atlanta was an up-and-coming city and wanted to get away from Chicago to focus more on family life and not so much on work,” Cheaa Mayfield said.

Curtis Mayfield’s Midas touch kept him busy. In 1976 he teamed with Aretha Franklin on the soundtrack to “Sparkle,” a musical drama about a 1950s female sibling vocal trio.

Mayfield reunited with Mavis Staples, lead vocalist of the Staple Singers, for “A Piece of the Action,” another film starring Cosby and Poitier, the next year. Later that year, he recorded the soundtrack to “Short Eyes,” a film about a man imprisoned for child molestation.

Cheaa Mayfield said his dad prioritized being easygoing and accommodating collaborators.

“He had good relationships with no animosity, creative differences while working, and they trusted him to take the lead. He and Aretha became pretty close, like brother and sister,” he said.

In 1978, Mayfield relocated his family and businesses to Sandy Springs permanently but kept his Southwest Atlanta property. He kept a low profile.

“He could go around anonymously, because he wasn’t really recognized by most people.”

“During the summer, we would go to the house in Southwest Atlanta because there was a pool there. It was a hangout spot for people who were prominent in politics and music,” Cheaa Mayfield said.

He said Muhammad Ali visited often.

Curtis Mayfield was approached about submitting music for “I’m Gonna Git You Sucka,” a 1988 spoof of Blaxploitation films directed by Keenen Ivory Wayans, but the deal fell through. Two years later, he became paralyzed after stage lights fell on him during a concert in New York. Mayfield released solo albums until 1996. He died from diabetes complications in 1999 at age 57.

Cheaa Mayfield, who manages his dad’s estate, said he hopes younger generations can appreciate the music legend’s artistic vision.

“They’ll hear a lot of samples and have no idea who’s written or performed it,” he said. “They need to know what Curtis Mayfield’s contributions are to music, culture and America.”

This year’s AJC Black History Month series marks the 100th anniversary of the national observance of Black history and the 11th year the AJC has examined the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and shaping American culture. New installments will appear daily throughout February on ajc.com and uatl.com, as well as at ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history.