Courtney B. Vance gives voice to the definitive W.E.B. Du Bois biography

For more than three decades, David Levering Lewis’ two-volume biography of W.E.B. Du Bois has stood as the definitive account of one of the most consequential thinkers in American history.

For nearly as long, actor, producer and activist Courtney B. Vance had been looking for the work in another form.

An avid consumer of biographies, Vance prefers to listen to them. For years, Lewis’ Du Bois volumes sat on his shelf unread: There was no audio version.

During a recent Harvard commencement weekend, Vance came close to meeting Lewis, who was receiving an honorary degree, but missed him.

When he finally tracked down him down, he asked, “Professor Lewis, why isn’t there an audio version?”

Lewis explained that the books were published when the concept and reach of audiobooks were far more limited than they are today.

“Courtney, what are you asking,” Lewis said. “Do you want to do it?”

“That’s not why I called. I just wanted an answer,” Vance told him. “But yes I do.”

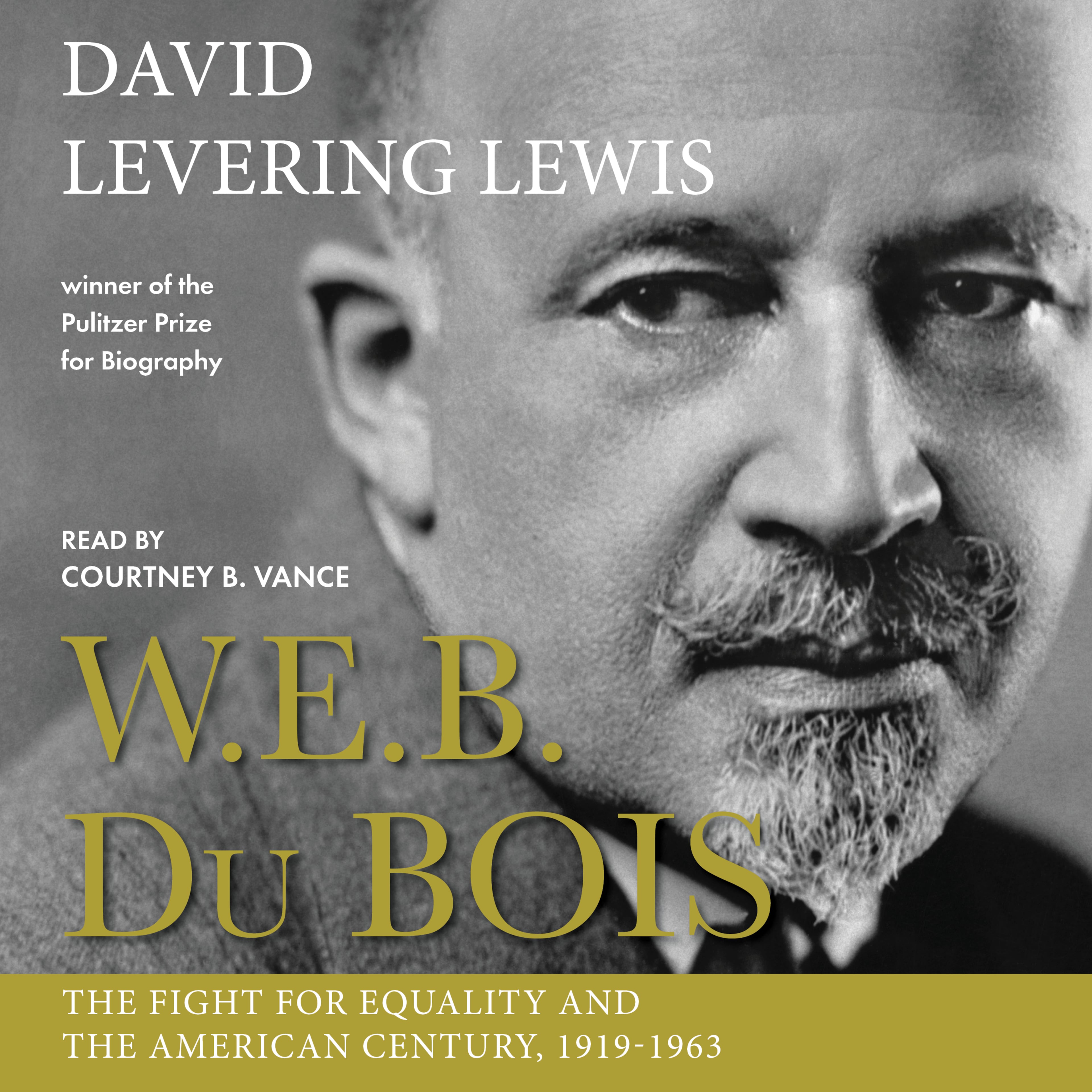

This week, Vance’s long effort will be complete with the Simon & Schuster Audio release of the audiobook edition of the second volume of Lewis’ biography, fully bringing Du Bois’ life and ideas to audio audiences and marking a significant moment for a work long considered essential reading in Black intellectual history.

Each volume earned Lewis Pulitzer Prizes.

“I was delighted Courtney wanted to be the voice of Du Bois,” Lewis told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution last week. “We agreed that it should happen.”

The first volume, also narrated by Vance, “W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868–1919,” was released last June. The second, “W.E.B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919–1963,” is scheduled for release on Feb. 10.

Published in 1993 and 2000, respectively, Lewis’ biographies reshaped understanding of Du Bois.

The first volume follows Du Bois from his birth in 1868 through World War I, tracing his rise as a scholar, his role in founding the NAACP, and the early articulation of ideas that would define modern Black political thought, including his work at Atlanta University, where he wrote the landmark “The Souls of Black Folk” in 1903.

The second volume spans the remainder of his life, from the killing of hundreds of Black people through the racial violence of the 1919 Red Summer, through his break with mainstream liberalism, his embrace of socialism, his federal indictment during the Cold War, and his final years in self-imposed exile in Ghana.

Du Bois died on Aug. 27, 1963. His death was announced the following day by Roy Wilkins at the March on Washington, moments before Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

But the shift from the written word to audio represents unfamiliar ground for Lewis.

“It’s a new terrain for me,” Lewis said, noting that he had not regularly listened to audiobooks until recently.

That hesitation, he added, came with a realization: “It’s a universe that really is profitable, engaging, and its reach, of course, is extensive.”

The release of the second volume comes exactly one year after Lewis’ most recent book, “The Stained Glass Window: A Family History as the American Story, 1790–1958,” a sweeping three-century narrative rooted in his own family history, with stops that include Roswell, Liberty County, Americus, South Carolina and Atlanta’s First Congregational Church. It’s available on audiobook.

For Vance, a lifelong student of history, audio is not a side format but how he “reads” — especially sprawling biographies of figures like Alexander Hamilton and King. “If I read it (in print form), that means I’m going to have to carry it with me and mess up my cover jacket, and I’m not doing that.”

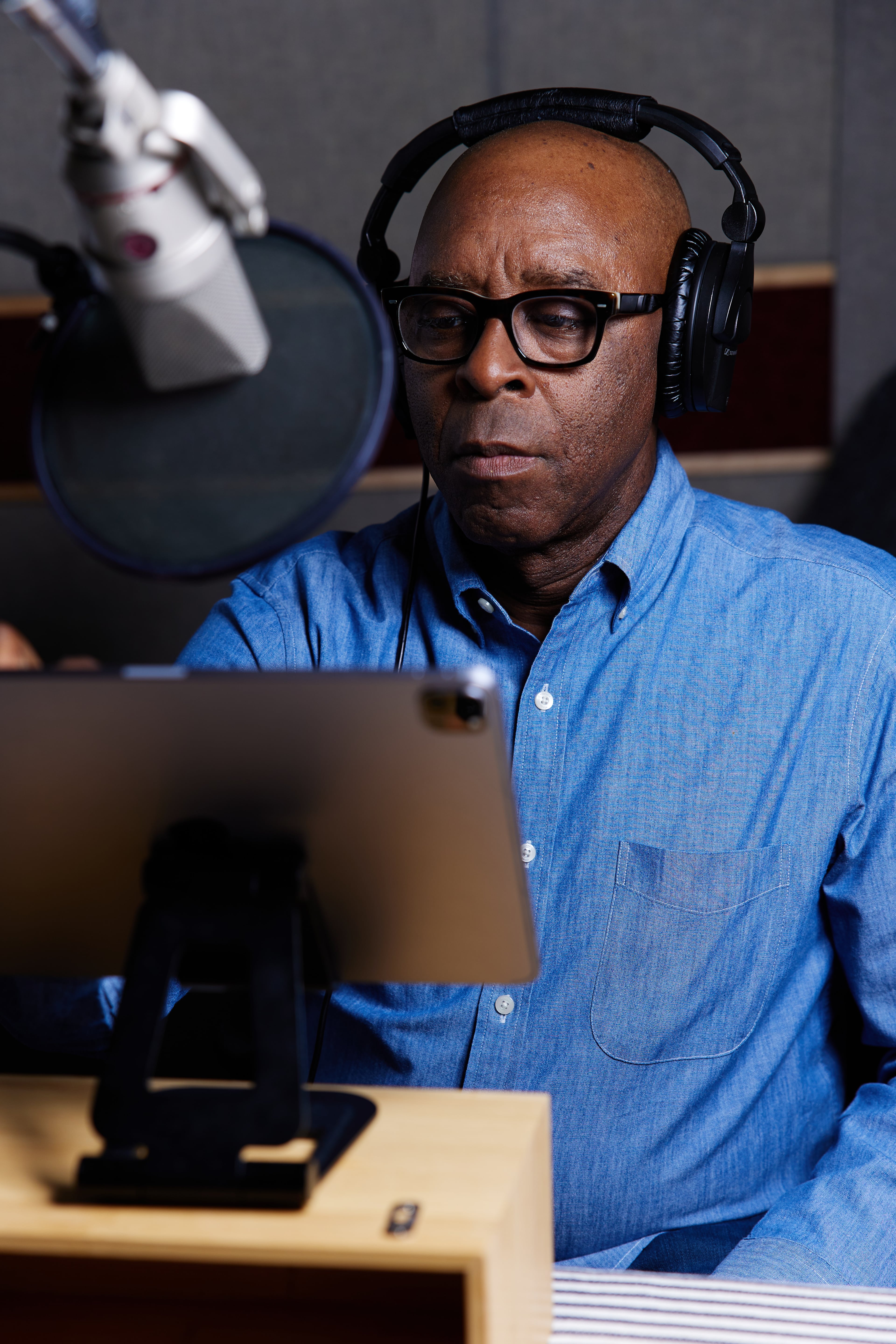

Vance, who has won a Tony Award and two Primetime Emmys, approached the narration as the most demanding role of his career, one that required embracing Du Bois’ full life, which was as complicated as it was brilliant.

“This is his entire life, cradle to grave. You see the complete man. No judgment,” Vance told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution last week. “Every 10 pages you’d stop because his personal life was so messy. He was an awful husband, an awful father, then he’d do something amazing and you’d say, ‘Oh my God, he’s incredible,’ and then two pages later you’d be mad at him again.”

Combined, the two biographies exceed 1,200 pages. Vance said he was only able to do about 20 pages a day.

“It’s so dense. If you push past that, it gets sloppy,” Vance said. “When we finished the second volume, we were like, what did we just do?”

Lewis’ understanding of Du Bois is more personal.

In 1948, at age 12, Lewis met Du Bois on the campus of Wilberforce University, where his father served as dean of the School of Theology. Lewis’ father, John Henry Lewis, also served two stints as president of Morris Brown College.

Lewis recited a speech he had delivered earlier that day, and Du Bois thanked him, saying, “You’ve done very well.”

Later that day, in a moment that shaped Lewis’ understanding of both Du Bois’ ideas and his voice, he listened as the scholar told an elite Black audience that the Talented Tenth had failed in its duty to serve the masses and must move beyond self-regard toward collective responsibility.

“It’s not a political voice,” Lewis said. “It’s not the voice of the hustings. It’s a voice of celebration, precision, and intensity.”

After listening to the completed first audiobook volume, Lewis said he heard that same sensibility in Vance’s narration and found that the performance already aligned closely with the subject himself.

“The pacing, the articulation, the voice register are ideal for W.E.B. Du Bois,” Lewis said, adding that the gravitas matters because Du Bois’ ideas remain sharply relevant today as a new generation examines his work.

Lewis joked that his books were so long his own children had never read them. Vance, a graduate of Harvard, said even on campus — where Du Bois became the first Black scholar to earn a doctorate — he knew nothing about him.

“Whether that’s on me or on the school, it doesn’t matter,” Vance said. “But now there is an opportunity. A new form of access. You can take your phone anywhere. Just download it and hit start.”

Vance’s production company, Bassett Vance Productions, which he co-founded with his wife, Angela Bassett, has also optioned the rights to produce a documentary extending efforts to reintroduce Du Bois to new audiences.

“We want to bring him back to his rightful place in the pantheon,” Vance said. “He was one of the greatest human beings in the 20th century. Bar none.”

This year’s AJC Black History Month series marks the 100th anniversary of the national observance of Black history and the 11th year the project has examined the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and shaping American culture. New installments will appear daily throughout February on ajc.com and uatl.com, as well as at ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history.